- The surge in mining activities for critical minerals in Africa poses a significant threat to the habitats of African great apes, including chimpanzees, gorillas, and bonobos. Deforestation, habitat destruction, and fragmentation disrupt their natural habitats, leading to population decline.

Key points:

- The surge of mining in Africa associated with the transition to clean energy threatens nearly one-third of the great ape population.

- Researchers determined that Guinea had the highest geographical overlap of ape density and mining practices.

- This study highlights that a shift away from fossil fuels requires careful consideration of regional biodiversity to protect species like great apes.

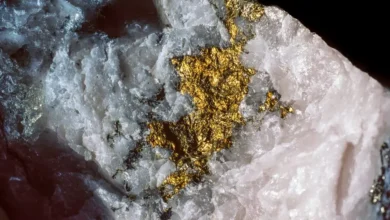

The rising demand for minerals and other rare earth elements required for the transition to clean energy has led to a surge of mining in Africa. New research, published in Science Advances, characterizes the impact of these mining practices on the great ape populations in Africa.

Researchers used data on operational and preoperational mining sites in 17 African nations. They defined 10 km buffer zones to account for direct impacts related to habitat destruction and light and noise pollution. They also defined 50 km buffer zones to characterize indirect impacts linked to increased human activity near mining sites.

The team integrated data on the density of great apes to determine how many African apes could be negatively impacted by mining. They then mapped areas where frequent mining and high ape density overlapped. This analysis revealed that the West African countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mali, and Guinea had overlaps of high ape density and mining. Guinea had the most significant overlap with more than 23,000—up to 83% of the ape population—directly or indirectly affected by mining activities.

Researchers also found that the threat of mining to great apes in Africa has been greatly underestimated. In fact, more than one-third of the entire population—nearly 180,000 gorillas, bonobos, and chimpanzees—is at risk.

The indirect and long-term impacts of mining are difficult to quantify because they extend beyond the boundaries of a project. In their mitigation efforts, companies rarely consider these risks and provide inaccurate impact approximations. Current offset or compensation schemes tend to last as long as mining projects are active despite the permanent impacts on great apes.

“A shift away from fossil fuels is good for the climate but must be done in a way that does not jeopardize biodiversity,” said study author Jessica Junker of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. “Companies, leaders, and nations need to recognize that it may sometimes be of greater value to leave some regions untouched to mitigate climate change and help prevent future epidemics.”