Commodity exporters rarely squeeze most of the value out of the raw materials they produce. Gulf countries are no exception. For the past half-century, the oil-and-gas-rich region has supplied fossil fuels to power global economic activity, but largely failed to industrialize beyond its role as a commodity exporter.

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants to challenge the status quo and bring a larger chunk of the oil value chain closer to home. The country’s state oil company, Saudi Aramco, joined forces with TotalEnergies in December 2022 to build a new $11 billion petrochemicals complex in Jubail.

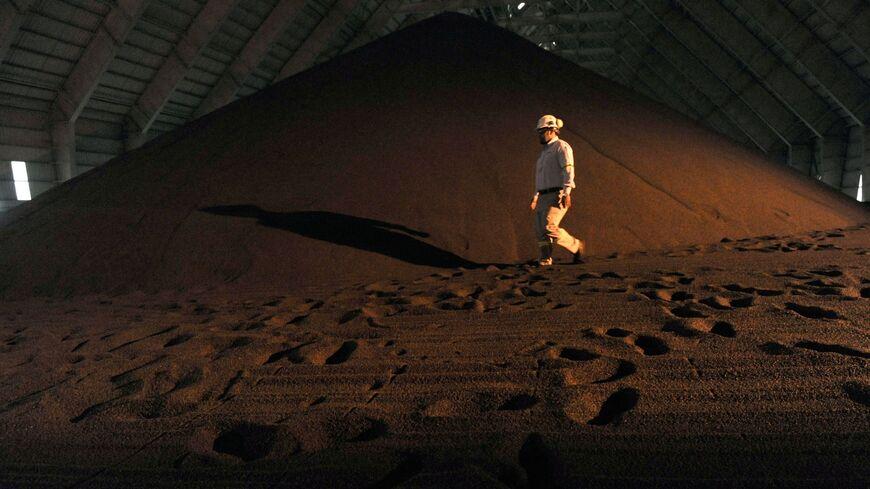

The kingdom also wants to dig out some of the $1.3 trillion of untapped mineral deposits that it claims to hold underground, including copper, phosphates, gold, zinc and uranium. In 2020, the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources became separate from the Ministry of Energy as Saudi Arabia aims to become an industrial and mining powerhouse.

Timothy Keating, director at the financial advisory firm Tanjun Capital, said the new department is doing “an incredible job” at putting Saudi Arabia on the mining map. “There is a realization that the mining industry can be a huge driver of the economy,” said Keating, who previously led Oman’s sovereign wealth fund’s private equity mining investment business.

Copper king?

Sylvain Eckert, head of metals and mining at the French-based Natixis Corporate & Investment Bank, said that Saudi Arabia has not yet conducted explorations or feasibility studies, “but there is quite a lot of potential for discoveries.” He told Al-Monitor that mining investors have mixed views, while the quality of deposits will need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Yet Riyadh is well positioned to cash in on rising global demand for copper, a critical conductor for electricity. “The world has never produced anywhere close to this much copper in such a short time frame,” rating agency S&P Global noted. Renewables-based grids, which accounted for 83% of the world’s new electricity generation capacity in 2022, are copper and aluminum-intensive. Since 2010, the amount of minerals needed for any new power generation unit has jumped by 50%.

Saudi Arabia holds an estimated $222 billion worth of copper reserves, and analysts say it is one of the key sources, along with Africa, to supplement traditional copper heavyweights like Chile, Peru, China, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the United States. The exploitation of new deposits is not a matter of choice. The ore grades of mined deposits are falling, which results in more energy needed to extract the same quantity of minerals. Chile’s average copper ore grade declined by 30% over the past 15 years.

Moving up the value chain

Saudi Arabia’s strategy outlines lessons that have been learned from half a century of fossil fuel export. The Minister of Industry and Mineral Resources said in November 2022 that Saudi Arabia does not want to “fall in the trap” of having its mineral resources processed elsewhere.

The country hopes to emerge as a manufacturing hub for electric vehicles, which require around 53 kilograms of copper per vehicle to produce, more than double that of an internal combustion engine car. “They want to develop onshore integrated value chains that are fed by Saudi resources and some offshore supply for minerals that are not available locally,” Keating told Al-Monitor.

Saudi Arabia is also home to large phosphate reserves — estimates vary, but 2018 figures put it at 7% of global proven reserves. It plans to boost phosphate fertilizer production to capture a quarter of the global export market. Saudi Arabia’s plan to exploit its uranium reserves to kickstart its civilian nuclear power industry is controversial given the role of uranium enrichment in developing nuclear weapons.

Saudi Arabia’s National Industrial Development Center (NIDC) lists exports of semi-finished and finished metal products among its top priority. Some examples include copper products such as tubes, bars and plates; aluminum products for automotive, aerospace and advanced industries; steel products like plates and rolled steel; and specialty steel castings and forgings.

As of late 2020, Saudi Arabia’s industrial cities are home to more than 1,290 factories producing mineral products. Besides boosting national pride and the “Saudi-first ideology,” locally made goods could also substitute for imported products that have long drained foreign exchange reserves. In 2020, Saudi Arabia spent roughly $11 billion to import 544,000 vehicles, its most imported product.

But by moving up the value chain, Saudi Arabia goes head to head with established global manufacturing hubs. For decades, China turned a significant share of Saudi Arabian crude oil exports into high-value products and consumer goods thanks to an industrial base and a supply of cheap labor. Saudi Arabia’s industrial capacities are expanding but remain in their infancy.

Amy McAlister, a Dubai-based lead economist at Oxford Economics, told Al-Monitor that shifting from commodity export to manufacturing will require building the appropriate infrastructure and logistics, available labor, access to supply chain inputs, technology and capital, and supportive government policy.

Saudi Arabia’s chief competitive advantage may lie in political considerations rather than in pure economic theory. China’s dominance over the global mineral supply chain — the fuel of the electrified economy — is a source of global concern. That gives geopolitical added value to Saudi minerals, raw or processed. Russia’s war against Ukraine has revealed why the United Kingdom “can never be too reliant on any one nation,” said UK business secretary Grant Shapps in January 2023. “That’s why it’s so key that we work with partners like Saudi Arabia.”

The icing on the cake of Saudi Arabia’s mining strategy is an attempt to exploit the global shift to regional strategic value chains. “I would not be surprised if there were a few lithium refineries developed in Saudi Arabia before the first lithium deposit comes on line,” said Eckert. Lithium batteries have become a popular power source for clean technologies such as electric vehicles.

In the first two months of 2023, Australian battery materials and technology company EV Metals Group unveiled plans to set up a lithium chemicals plant in Saudi Arabia by 2026, and a Saudi startup raised $6 million in funding to extract lithium from the Red Sea.

Put words into action

Mining is a notoriously cyclical and capital-intensive industry, and Saudi Arabia is reluctant to shoulder the capital expenditures alone. The country aims to attract $170 billion of investment in the mining sector by the end of this decade.

The kingdom’s top-down decision-making allows it to ignore any local opposition and boasts 90 to 180 days to issue mining licenses in a bid to lure investors. Globally, it takes 16.5 years to move from mining discovery to production, according to the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization in Paris.

“They are doing all the right things. … Saudi Arabia is certainly underexplored and underdeveloped from a mining perspective, but it is starting to rub shoulders with the bigger players in the industry,” Keating said.

At a January 2023 mining forum in Riyadh, local entities signed deals to open the kingdom to international miners and invest up to $15 billion in global mining assets.

Still, the crown jewel of Saudi Arabia’s mining ambition is Ma’aden, the Gulf’s largest miner, with 2022 revenues of $10.7 billion. The company is majority-owned by the Public Investment Fund, the crown prince’s financial vehicle to diversify the economy. Ma’aden did not respond to a request for an interview.

Saudi Arabia’s political regime might insulate miners from not-in-my-backyard activism, but Ma’aden will still have to contend with the arid environment. The water requirements of mining and mineral processing pose a challenge, as Saudi Arabia is ranked the world’s eighth-most water-stressed country. Unprocessed seawater would require special pipelines and adjustments and does not solve the problem of byproducts like acidic discharges. The National Center for Environmental Compliance, did not respond to a request for an interview.